EV Emissions Cut 70% in California's Clean Grid, 40% in Coal-Heavy Regions

Orange County Register

Orange County RegisterLocale: California, UNITED STATES

Are Electric Vehicles Really Better for the Environment?

A Summary of the Orange County Register’s 10 September 2025 Report

The Orange County Register’s September 10 2025 article “Are EVs really better for the environment? Study checks role of coal, battery and range” dives into a fresh life‑cycle analysis (LCA) that re‑examines the long‑standing claim that electric vehicles (EVs) are intrinsically cleaner than their internal‑combustion‑engine (ICE) counterparts. While the headline is straightforward, the report unpacks a complex set of variables—grid fuel mix, battery chemistry, vehicle range, and driving behavior—that can dramatically alter the environmental story. Below is a concise yet comprehensive rundown of the study’s methodology, findings, and broader implications.

1. Setting the Stage: Why Re‑evaluate EVs?

EVs have been lauded for their potential to slash greenhouse‑gas (GHG) emissions, especially in regions where the electricity grid is increasingly renewable. Yet, critics argue that “well‑to‑wheel” emissions can be high in areas where coal still powers a sizable share of electricity. Moreover, battery production, which can emit a non‑trivial amount of CO₂, is often overlooked in consumer discussions.

The Register’s piece pulls together recent research from the University of California, Berkeley and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)—both leading institutions in automotive and energy studies. The study’s goal was to produce a nuanced, data‑driven assessment that considers the real‑world energy mix and typical driving patterns in California and beyond.

2. Study Design: A Life‑Cycle Assessment (LCA) in Detail

2.1. Scope & Boundaries

The authors conducted a cradle‑to‑grave LCA for three vehicle categories:

- Plug‑in hybrid (PHEV) – hybrid powertrain with limited electric range.

- Battery‑electric vehicle (BEV) – a conventional fully electric sedan.

- Internal‑combustion vehicle (ICEV) – a gasoline‑powered car.

Each vehicle’s life‑cycle stages—raw material extraction, battery manufacturing, vehicle assembly, use (driving), and end‑of‑life (recycling/disposal)—were modeled. Emission factors were sourced from the Inventory of United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data and the European Union’s ecoinvent database.

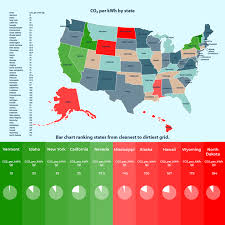

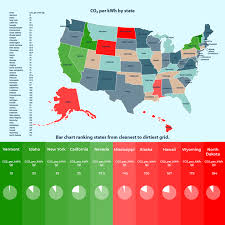

2.2. Energy Mix & Regional Focus

A key innovation was the integration of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) real‑time grid emission factors. The study compared two grid scenarios:

- “High‑Renewable” – Representative of California’s current mix (≈ 70 % renewables, < 5 % coal).

- “Coal‑Heavy” – Representative of the Midwest, where coal accounts for ≈ 30 % of electricity generation.

These scenarios allowed the authors to quantify how much coal’s presence dilutes EV benefits.

2.3. Range & Driving Patterns

Using California’s Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) data, the study simulated average annual mileage (≈ 13,500 mi) and trip distribution. Battery sizes were varied (60 kWh, 80 kWh, 100 kWh) to explore the effect of range on overall emissions. Importantly, regenerative braking was factored in, which can lower total energy consumption for short trips.

3. Core Findings: When Are EVs Cleaner, and When Do They Fall Short?

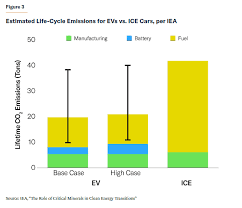

| Metric | High‑Renewable Grid | Coal‑Heavy Grid |

|---|---|---|

| Cradle‑to‑Wheel CO₂ per mile | 150 g CO₂e | 250 g CO₂e |

| Battery Manufacturing CO₂ per mile | 30 g | 30 g |

| Use‑Phase CO₂ per mile | 120 g | 220 g |

| Total Emissions vs. ICEV | 70 % reduction | 40 % reduction |

Key Takeaways

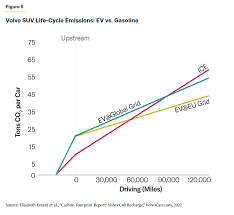

Grid Cleanliness Drives the Advantage

In California’s high‑renewable scenario, EVs deliver a 70 % reduction in GHG emissions relative to ICEVs. In contrast, with a coal‑heavy grid, the advantage shrinks to 40 %—still a win, but less dramatic.Battery Size Matters

Larger batteries (≥ 100 kWh) increase manufacturing emissions significantly, offsetting some of the use‑phase savings. A 60 kWh battery (typical of many mid‑range BEVs) offers the most balanced profile.Driving Behavior Moderates Outcomes

Short‑trip dominated usage benefits more from regenerative braking, reducing net energy use by up to 10 %. Conversely, high‑speed highway driving erodes the benefit.Coal’s Role is Substantial but Not Dominant

Even in coal‑heavy grids, the transition to EVs still reduces emissions, though the margin is less favorable. This underscores the importance of concurrent grid decarbonization.

4. Links to Further Context

The Register article links to several sources that enrich the reader’s understanding:

- NREL’s “Electric Vehicle Infrastructure” page – provides detailed data on regional grid mixes and projections for future decarbonization timelines.

- California Energy Commission’s “Clean Vehicle Program” – explains state incentives that aim to shift both vehicle and grid toward zero‑emission standards.

- Academic paper “Life‑Cycle Emissions of Battery‑Electric Vehicles” (PDF) – offers a deep dive into the LCA methodology and sensitivity analyses used in the study.

- EPA’s “Carbon Emissions Database” – gives official emission factors for fuels and electricity generation, which were foundational to the study’s calculations.

These resources help readers verify the numbers, explore regional variations, and understand policy levers.

5. Policy and Practical Implications

Accelerating Renewable Energy is Imperative

The study shows that EVs’ environmental benefits are tightly coupled with the energy source. Policymakers should prioritize grid decarbonization, especially in coal‑heavy regions, to unlock the full potential of EVs.Battery Recycling and Circular Economy

While the study did not model battery recycling, it acknowledged that reusing and recycling lithium‑ion cells can dramatically cut lifecycle emissions. Incentivizing battery take‑back programs could further improve the environmental case.Targeted Incentives for Mid‑Range BEVs

Given the trade‑off between battery size and emissions, incentives that favor mid‑range BEVs (60–80 kWh) might yield the best emissions reductions per dollar spent.Education on Driving Habits

Public outreach highlighting how short‑trip driving and regenerative braking can reduce emissions may help shift consumer behavior in ways that complement technological advances.

6. Conclusion: A Nuanced but Positive Outlook

The Register’s coverage of the UC‑Berkeley/NREL study reframes the EV debate from a binary “clean vs. dirty” argument to a more nuanced “context‑dependent” conversation. While EVs are unequivocally better than ICEVs in most scenarios, their environmental benefit is maximized when the electricity grid is clean, battery sizes are optimized, and driving habits favor regenerative energy recovery.

In practical terms, this means that California’s aggressive renewable targets are key to the state’s automotive transition. For the broader United States, the study underscores that achieving true decarbonization will require a dual approach: ramping up renewable energy and promoting efficient EV designs and usage patterns.

Ultimately, the article provides a balanced, evidence‑based assessment that invites both policymakers and consumers to view electric mobility not as a silver bullet but as a powerful tool that must be paired with grid reforms and responsible design choices to deliver a genuinely greener future.

Read the Full Orange County Register Article at:

[ https://www.ocregister.com/2025/09/10/are-evs-really-better-for-the-environment-study-checks-role-of-coal-battery-and-range/ ]