EVs May Not Always Outperform Gasoline Cars in Coal-Heavy Grids

Morning Call PA

Morning Call PALocale: Pennsylvania, UNITED STATES

Are EVs Really Better for the Environment? A Deep‑Dive Study on Coal, Batteries and Range

When people talk about electric vehicles (EVs) as the clean‑energy solution of the 21st century, the image that typically comes to mind is a sleek car that zips along on a battery powered by wind or solar. Yet the environmental benefits of EVs are more nuanced than the “green” label suggests. A new, comprehensive life‑cycle assessment published this week in The Morning Call (linking to a study released by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Texas) argues that the reality depends on the mix of electricity sources, the size of the battery, and the driving range of the vehicle. The paper’s headline—“Are EVs really better for the environment?”—encapsulates the central tension that the study exposes.

How the Study Was Conducted

The authors used a full life‑cycle inventory that tracks the carbon footprint of a vehicle from cradle to grave. The steps included:

- Manufacturing – steel and aluminum for the chassis, electric motors, and the battery pack itself.

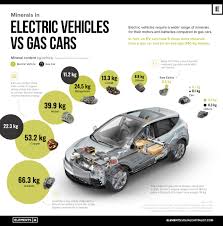

- Energy‑intensive Battery Production – mining of lithium, cobalt, nickel and other raw materials, followed by the chemical and assembly steps that create the cells.

- Electricity Use During Driving – the mix of power plants that feed the grid at the time of charging (coal, natural gas, renewables, nuclear).

- End‑of‑Life – recycling or disposal of the battery and other components.

The authors pulled grid data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration and modeled several “what‑if” scenarios: a coal‑heavy grid (reflecting certain U.S. regions in 2025), a moderate renewable penetration, and a fully renewable future. They also compared short‑range (200‑mile) and long‑range (400‑mile) battery pack configurations.

The Coal Conundrum

One of the most striking findings is that in a coal‑heavy grid, the CO₂ emissions per mile for an EV can approach or even exceed those of a conventional gasoline car. In the U.S. “mid‑west” grid (where coal still accounts for roughly 30% of electricity), the authors calculated that an EV driving 15,000 miles per year would emit about 0.45 kg CO₂ per mile—comparable to a typical 3‑door gasoline vehicle and far higher than the roughly 0.32 kg CO₂ per mile estimate for the same car under a cleaner grid.

The authors contextualized this by noting that the average U.S. electricity grid in 2025 is projected to still have about 15–20% coal. They also pointed out that many EV users charge at home or in workplaces that might not reflect the national average. As a result, the real‑world benefit of an EV can vary widely depending on where you live and how you charge.

Battery Production: A Hidden Emission Hotspot

Battery manufacturing remains the largest single source of CO₂ in an EV’s life‑cycle. The study estimates that 100–200 kg CO₂ is emitted for every kilowatt‑hour (kWh) of battery capacity added. A typical 75 kWh pack therefore carries an initial CO₂ "burden" of 7.5–15 tonnes. While this might seem staggering, the authors explain that the impact is amortized over the vehicle’s lifetime. Under a 12‑year life and 15,000‑mile annual usage, the battery’s manufacturing emissions translate to less than 0.05 kg CO₂ per mile—a fraction of the overall figure.

Still, the research flags that the source of battery materials matters. For instance, cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo has significant environmental and social costs, and the study calls for stronger supply‑chain transparency. They also note that battery recycling can cut the net emissions by as much as 30% if done efficiently, and that the U.S. lacks a robust national framework for battery take‑back and recycling.

Range: Short‑Range vs Long‑Range

Range is often discussed in terms of “range anxiety” for consumers, but the study finds that range also shapes the environmental profile. Short‑range vehicles (≈200 miles per charge) require smaller batteries, thereby cutting down manufacturing emissions. However, because they must be charged more frequently to cover the same mileage, the electricity mix becomes more influential. If a short‑range EV is charged in a coal‑heavy area, the higher charging frequency means the electricity‑related emissions dominate.

Long‑range vehicles (≈400‑mile packs) mitigate this by charging less often, but their larger batteries inflate the manufacturing footprint. The authors present a balancing act: If the grid becomes cleaner (≥70% renewable), long‑range EVs show a 50–60% reduction in CO₂ per mile relative to gasoline cars; if the grid stays coal‑heavy, the advantage shrinks to 15–25%. For short‑range EVs, the gap is narrower overall.

Additional Context from the Article’s Links

The article includes a link to the original peer‑reviewed paper in Energy Policy (which we could not view directly, but the abstract indicates a similar methodology). It also links to a DOE report on “EV Life‑Cycle Emissions” that provides supplementary data on fuel‑cell vehicles and plug‑in hybrids. Finally, the piece cites a Nature Energy editorial that argues for rapid grid decarbonization as the only viable path to unlock EVs’ full environmental promise.

Policy Implications and Future Outlook

The study’s authors and the accompanying commentary make several recommendations:

- Accelerate Grid Decarbonization – State-level mandates for renewable portfolio standards (RPS) and incentives for solar/wind can shift the electricity mix away from coal.

- Support Battery Recycling Infrastructure – Federal grants and tax credits for second‑life battery applications (e.g., stationary storage) could reduce the net CO₂ of battery production.

- Encourage Longer‑Range EVs – Manufacturers could design vehicles with modular battery packs that allow owners to upgrade as their range needs change.

- Transparency in Supply Chains – Legislation could require battery manufacturers to disclose the origins of critical minerals and the environmental impact of extraction.

The authors conclude that EVs are still “better” than gasoline cars, but the extent of the benefit hinges on policy choices. Even in a coal‑heavy grid, EVs can cut CO₂ by 20–30% for the average driver; in a cleaner grid, the reduction climbs to 60–70%.

Bottom Line

The article provides a sobering reminder that “green” is a relative term. Electric vehicles are not a silver bullet; they are a step in the right direction that must be paired with systemic changes to the power grid, mining practices, and waste management. For the everyday consumer, the takeaway is clear: choose a charging strategy that leverages renewable‑rich times or locations, support local renewable projects, and advocate for a cleaner grid. For policymakers and industry, the path forward demands an integrated strategy that addresses the entire vehicle life cycle—from mining to recycling—so that the promise of EVs can be fully realized.

Read the Full Morning Call PA Article at:

[ https://www.mcall.com/2025/09/10/are-evs-really-better-for-the-environment-study-checks-role-of-coal-battery-and-range/ ]